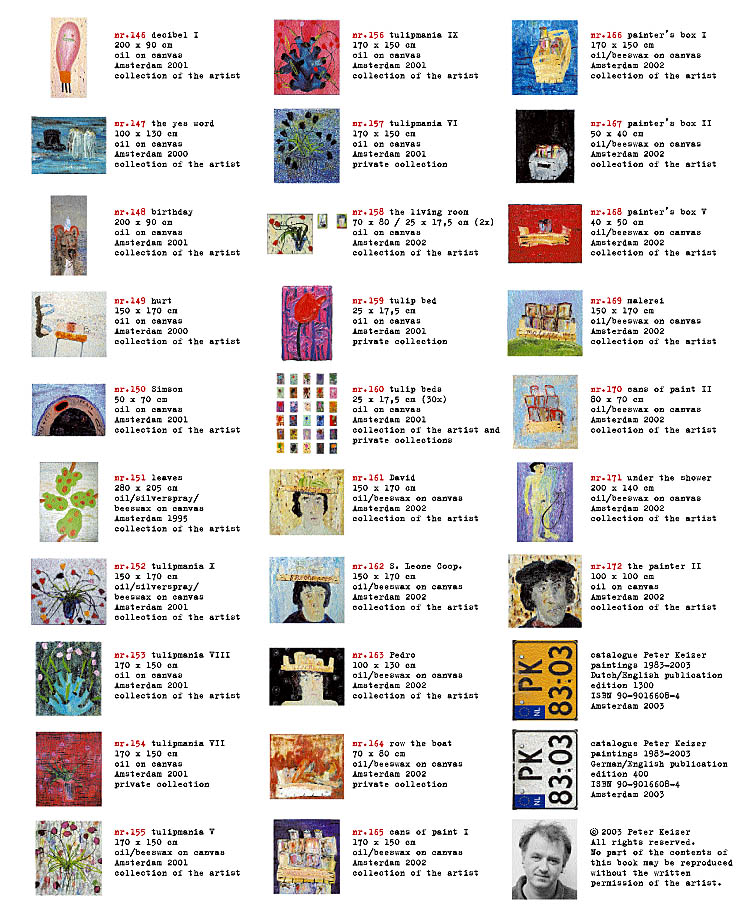

Catalogue ‘PK 83-03’

Click on the images for enlargements.

This catalogue provides a 20 year overview of the artist's paintings and is accompanied by a text by Helga Geyer-Ryan.

On this page you can view a number of sample photos, the index, and the book's text.

Helga Geyer-Ryan

THE PAINTER'S UNIVERSE OF PETER KEIZER

(translation Jane Hall)

The painter Peter Keizer's life-story could start like this:

Once upon a time there was a little boy called Peter who lived in Amsterdam. His father was the painter Jerry Keizer and the little boy wanted to be a painter too, since it was clear that anyone called Keizer was sure to be a high-flyer. As high as Peter's grandfather, Grandpa Grape, had flown in the thirties when he was known in England as "the Flying Dutchman" and as "de vliegende keep" (or Flying Keeper) in Holland. Because Grandpa Grape, whose real name was Gerrit Keizer, was goalkeeper at Ajax in Amsterdam and at Arsenal in London at the same time. He didn't just fly through the air in front of goal, he flew backwards and forwards between Holland and England every week. Later he became a greengrocer and every time he visited his grandchildren, he brought some grapes and so was called Grandpa Grape.

Grandpa Grape is immortalised in "Hommage aan opa Druif" ("Homage to Grandpa Grape" picture nr.100) from 1996. It is a gigantic triptych, or rather a pentatych, as two panels depicting hands (the keeper's hands?) hold the triptych together from either side. It now hangs in Ajax ArenA Stadium. The paintings created in line with this homage are of fairy-tale goblets in the softest of shades (nr.97-99). It is now clear what the sum of Peter Keizer's painting work defines: the emotional involvement in his own experiences and life-story.

From an early age Peter Keizer wanted to join his father in the studio. He wanted to help his father and start working himself. But the greatest pleasure, says Jerry Keizer, came from taking the small paintings his father had rejected off their frames and then to see something new created from nothing. This dual aspect of creation and destruction sets the tone for Peter Keizer's work. Love is coupled with the associated health-risks (nr.70-72), the cuddly teddy bear is the prize for a shot hitting the target (nr.51-56); the dog is shown as a cherished pet (nr.2-4,129-130) and as aggression armed to the teeth (nr.9-10).

This sort of ambiguity is associated with the zodiac sign of Gemini: Peter Keizer was born on June 16th 1961. Moreover June 16th is Bloom's Day, the day on which Leopold Bloom from Joyce's U l y s s e s wanders through Dublin like Odysseus once roamed around the Mediterranean. "Always on the move", this can be said of water in the rivers and seas, whether it's the Liffey, the Amstel, the Mediterranean Sea or the Atlantic Ocean. Movement leaves traditions behind, it is change, putting things in perspective, criticising and destroying the old. These attitudes can be found in Peter Keizer's paintings in their irony, humour, and love for the small, the insignificant and trivial. Irony is an attitude that transfers or "trans-ports" the pictorial traditions of exalted themes to the world of ordinary,everyday things. The universe of his work primarily consists of objects and these objects belong to the most concrete things of daily life.No historical panoramas, no landscapes, no architecture, no nudes, no portraits, no group scenes, no allegories, no mythologies, no cities, no stars.

For Peter Keizer, it is the objects that are central to the paintings rather than the meaning of the subject. The importance of the object is emphasized not only in psychoanalysis, but also sociology (Bruno Latour), semiology (Roland Barthes) and philosophy (Martin Heidegger, Walter Benjamin). In "Vom Ursprung des Kunstwerks" Heidegger classifies objects in the world into the things (nature), tools (products made by people from things that are necessary to survival such as machines) and works of art. Because of their usefulness, the truth about tools and things is usually hidden from sight, but it is revealed in works of art. Things and tools give testimony to man's actual state of being; they are the manifestation of the relationships of man with man and of man with nature. Heidegger uses the example of Van Gogh's farmer's shoes to illustrate this. An understanding of mankind in the world lurks behind their usefulness.

Just as the shoes are simple for Van Gogh (consider the other simple things such as a bed and a chair), so are the objects on Peter Keizer's canvasses. They come from the world of tools, from the world of things made by people. And in his case they are often the simplest, or earliest, or most important, in short the most archaic for someone living in Northern Europe. Matches (nr.78-82), electrodes (nr.143-146), chimneys (nr.18-27) and plugs provide heat and light, wells (nr.16-17,30-31), jugs and cups place water at our disposal, excavators open up the ground (nr.30), in studios and living rooms (nr.131-133), on mattresses (nr.43-47,49-50) and chairs people live and work, saws, knives and scissors (nr.6-8) are used to cut, zips are closed, man does not live by bread alone, he also plays with chess pieces (nr.85-88), boxing gloves (nr.105-108), football boots (nr.100), dancing shoes (nr.101-103), skates (nr.128), history, including his own history is found in tulips (nr.152-160), the Soldier of Orange (nr.139), paintbrushes, painter's boxes (nr.165-170), heads of painters (nr.89-90,172).

In their representation these archaic things are subjected to a painting method that reinforces the impression of the archaic. Simple, reduced forms, coarse materials, large areas of colour, often monochromatic, colour layers woven through each other, thick layers of paint applied with a palette knife. The paintings often seem to have been hastily and roughly placed on the canvas. The irony lies in this fascination for the material that denounces the falsely exalted, the artificial, the pretentious and lofty. Peter Keizer shows himself to be not only an archaic but also a contrary painter. The way in which he is dedicated to this simplicity is possibly his most Dutch characteristic. The fact that he is looking for the effect of this simplicity and at the same time has his colours light up from the inside, shows, besides his irony, also a great love for the world as depository for the things. This is exemplified when examining "The kiss" (nr.93).

Because of the title it can be placed in the context of Rodin's famous sculpture from 1886 "The Kiss". Perhaps the sculpture is an expression of the ideal at that time of romantic love that is successful for the last time; it can only succeed because all links to the world and the time have been cut off. The couple are archetypically naked and closed in on themselves. If these dimensions should be restored to the romance without any reflection on this, the "timeless" ideal can only become corrupted. This can be seen in Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo". In the central kissing scene the internal dynamics are transferred "trans-ported" to the external dynamics of the camera that encircles the couple kissing in a movement of 360 degrees. But, precisely because it has to conceal so much, this kiss leads to the inevitable downfall of the lovers. The ideal refuses to materialise. Peter Keizer interprets this real-life impossibility by reducing the visual material to its absolute minimum. What remains is just heads, "quoted", one could say from children's drawings: long hair for the woman, short hair for the man, and then bigger eyes and a redder mouth for the woman. The kiss seems to be even more of a quotation because the kiss itself is a painting within a painting. In addition there is the reference to the painter himself in the form of a paintbrush under the man's head. Modern art, such as represented by the multiple perspectives of Matisse and Picasso, is likewise quoted here. The small crown under the woman's head ironically quotes the queen in card games and chess so that the unreal nature of love, the quotation characteristic, the game-like quality of love and painting simultaneously become clear.

Because the kissing couple already exist as two separate portraits, "The painter" (nr.91) and "His wife" (nr.92), we can conclude that it is actually two paintings that are kissing. Two paintings are kissing each other in a painting on a painting. The couple kissing are the painter and his wife. Which painter? Peter Keizer? Every painter? Any arbitrary painter? The apparent archetype of the painter and his wife merely consists of a sort of shorthand, a clich for "artistry", such as the Bohemian black moustache, the black "French" locks, the paintbrushes and their "existence" on the painting itself. Peter Keizer thus uses humour to turn upside down a world that surely seemed to be the dualist segmentation into reality and art, authenticity and imitation, inside and outside.

The same thing happens in other paintings. In "The painter I" (nr.90) the painter has a stereotypical beard and wears a Basque beret - Italian renaissance or French Montmartre to show that he is a painter. In "Philip Guston in his art gallery" (nr.89) the Canadian painter Philip Guston, who Peter admires, only consists of a second-hand symbol: as a name and as a self-portrait in his gallery. Similarly in "Eye contact" (nr.94). This love "inflamer" comprises two paintings hanging facing each other each with an eye. The paintings are "looking at each other". And "Saying yes" (nr.147), still probably the high-point of a love story, merely quotes the wedding ceremony in a metonymic shorthand of veil and top hat.

The cycle "Bollenrazernij" or "Tulip bulb frenzy" is an allusion to the sharply price-inflating trade in tulip bulbs in the seventeenth century and the associated aspiration to propagate black tulips. The "Tulip bed" (nr.160) from the cycle is actually not one painting but a series of sixty-four different paintings each with one tulip which are hung together. It is a critical response to this mass delusion, but at the same time an homage to the beauty of tulips, expressed in the ornamental arrangement and the supernaturally brilliant colours. These tulips not only provide a broad grin at the financial greed and the floral clich of a national and parochial aesthetic - "Tulips from Amsterdam" - but also display genuine admiration for the wonderful results from an amicable symbiosis of earth and world, nature and mankind.

This naturally human, dualist method, born of irony and love, characterises all of Peter Keizer's work. A fractured outlook, a child-like yet experienced outlook, chooses a simple thing as object. This object becomes alienated. It is worked on to such a degree that those daily and automatic perceptions of the object that have thereby become"blind" are disrupted. The Russian formalists were the first to systematically develop a similar aesthetic. The object that has become lost under its function emerges as such despite its oblivion. (Heidegger regarded this blind condition of the world that had become automatic as "being forgetfulness". Despite their lack of memory, the work of art brings the being of the things back to the forefront. It is the truth in the work of art.)

In no longer perceiving the objects as the state of their forgotten being, time becomes empty for people, it becomes dead time. Alienation must prevent the dying of unlived time. Because perception is made more difficult and understanding is slowed down, the object and thereby man's time is awoken in a new life. It is "trans-ported" to a state similar to childhood. Here, worldly things again evoke amazement and lively perception. This child-like adventure in association with the world is what art and artists want to give back to us.

An aesthetic outlook - and since Kant this is "selflessly agreeable", in other words detached from the functional connections of the things - is all that is needed to release an object from its context in order to experience it as a self-contained unit with its own value. Choosing an object therefore becomes an act of isolating it. The selection can then fall on a portion of the object. The cut-out is greatly enlarged, "blown up": nr.6 ("Teeth"), nr.8 ("The barber business"), nr.15 ("A pile of stones"), nr.78 ("Elastoplast"), nr.18-27,29 (chimneys series), nr.43-47,49-50 (mattresses series), nr.30 ("Dredging"), nr.33-34 (boxes), nr.51-57 (the bears series "Are, they, they"), nr.58,61-66 (the "Hommage aan Yves Klein" series). This technique can be seen at its most extreme in the lucifers (matches) series (nr.79-84), because these are already so tiny. The alienation effect of these combined methods is so powerful that one needs the title in order to identify the objects and enjoy the effect.

One of these objects is the exact opposite of the classic object in the still-lives from the Old Dutch Masters. Roland Barthes alludes to this in a study of the (admittedly literal) objects in the work of Robbe-Grillet. In the Old Masters the silky sheen on the items, on the glasses, the oysters, the wine and the metal suggest that the (skin) surface can be synaesthetically seen and felt simultaneously, but the underlying essence of the things, their reality, becomes further shrouded in darkness.

Peter Keizer's use of materials conversely "clears" the objects. They are reduced to the two dimensions of the canvas, flattened by consistently ignoring spatial perspective. The flat objects are further simplified to basic shapes so that, when they are enlarged, they look like archetypes and when they are scaled down they appear as a sort of short-hand or signs. Scenarios are frequently taken apart, and the separate parts then combined with other fragments. Decomposition can be seen for example in the paintings nr.131-133. Examples of repeating separate elements here are the cat's hairs standing on end in nr.69 which also return in the tongues of flame and as a crown under the female profile in nr.93. Grandpa Grape's shoe (nr.100) is found again in nr.101-103 and 128. The stove from nr.127,129-132 appears two years later in 133.

Peter Keizer has found another means for clearing the object in the serial-like variations of his themes. A series is always susceptible to the prominence of one of its parts. In this book series can be found of pregnant bears in "Homage to Yves Klein", shooting gallery bears, matches, artist's materials (nr.161-170), the girl and fellatio (nr.117-123, and spread), mattresses, electrical valves and light bulbs (nr.143-146), chess pieces, tulips and the series called "Series 7" (nr.134-140) the motifs for which can only be found in the subtitles.

The aesthetic of clearing the classic object is appropriate to Peter Keizer's more encompassing, iconoclastic gesture. The most obvious example is "Plopper" ("Plunger", nr.142). His motto: "Distance from your own work" originated during a workshop with Jörg Immendorf. Peter Keizer has also distanced himself from Art with a capital A as something lofty and exalted and has replaced this with humour and the joy of creation. And distance from his own painting has changed into irony in the choice of his motifs and his use of materials.

Apart from the methods described to clear the thematic object, the use of artistic materials and resources is also directed towards making the object empty, thus reducing the painting itself to a thing amongst other things. Heidegger appreciated that art is also primarily a thing, such as a sack of potatoes or coal in the cellar. But if the thing's mode of being is only revealed in the work of art, then the work of art must also say something about itself. And not only that. It must go beyond the recognition of the dimension of truth in relation to the things and evoke its own characteristics as a thing.

These dual terms of reference can be seen in every successful work. First there is the "fecit" for each work: the signature and artistic handwriting of the artist ("Style c'est l'homme même"). In Peter Keizer's work the substance that is extracted from the "inside" on the paintings (the clearing of theme and art) is added again from "outside". The destruction of the sheen on the skin of the things (as described earlier) is repeated in the destruction of the skin of the painting itself, but the painting thereby gains a new, "rough" substantiality like a thing.

The oil paint is applied like pastels, often in several layers and colours on top of each other. Thick brushes draw tracks through these restless surfaces and lay the canvas bare once more. Some parts of the canvas are never even touched ("Series 'unfinished' paintings I", nr.102). In these scraped and already drying surfaces Peter Keizer will apply new reliefs, which are worked in using paint roller, palette knife or spray gun. Sometimes foamy crests of dried paint are found on thick edges or in gaps. These techniques give back to the object as a painting what was taken from the object as a motif: a third dimension. His paintings are on the point of growing into the space, ready to produce a nose or a body.

Peter Keizer made a long, narrow object dedicated to love. According to its shape it is a cross without a crossbar. It comprises an arrow and a heart and light silver colour and red on it. The highpoint of this - in the truest sense of the word - is an empty, silver-coloured aluminium paint-tube. Peter Keizer has pressed it into the half-dried heart. The message here is twofold: love is artificial; it consists of symbols that both represent and also at the same time arouse the feeling - in spite of their stereotyping but because of their powerful appeal to the senses. Love thereby becomes a concrete thing, just as present as any other thing, even though it is ultimately a cultural construction. Love is not only kitsch, it is beautiful, heavenly even, is what the work of art is saying through its design and brilliant colours.

The photographic transitions between the sections of this book also show the painting as a thing. On the photos the artwork is packaged, carried off, loaded up and "trans-ported", just like any other product. It is mercilessly dragged along in a hiatus of irony, in the intervening space between work of art and thing, distance and love, original and copy. The book explicitly relates to the painter himself, it is his thing, his photo album. The cover depicts the painter's initials formed by the letters on the number plate of a means of "trans-port". The paintings start with "Billy & Peter" and end with the painter's box in Italy, the painter's materials, under the shower (the naked painter?) and the painter. The book is also about the tradition of his metier and his language. The illustration on the inside of the cover shows a girl's head with the title "Ceci est une pipe", an allusion to a painting by Magritte "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (the depiction of the pipe is after all only painted and not the pipe itself) and also the Dutch expression for fellatio: "to pipe someone".

Nevertheless, notwithstanding all the irony and all the humour, the beauty of the paintings continues to captivate the eye. The love for the object is expressed in the composition of the forms and the colour scheme and brings with it a positive "yes" to the world and the life of things. The delight of looking enables the viewer to experience this power of the things.

Peter Keizer portrays them brilliantly, placing them on different coloured backgrounds that remind one of the art of icon painting. It is the combination of colours that creates this effect. In painting nr.4 for example the red of the background is intensified by the dark brown of the dog's coat and vice versa - one is tempted to say the brown begins to shine like silk. In painting nr.55 the red and blue reinforce each other because they are so vividly represented. Then it is again the combination of primary and pastel colours (nr.159) or the addition of bees wax to increase the transparency of the colours that provides an unexpected feast for the eyes. Or the middle of the painting is almost imperceptibly lightened to such a degree that it appears as if there is a light-source behind the canvas (nr.95, 151-152). The best example is the plunger ("Plopper", nr.142). Even this actually dirty article is ultimately a "trans-port" means used against blocked drains and any stagnation. That is why it is beloved and why it is festively presented to us on a silver tray, one could almost say, on a crimson base with a grid of silver buttons.

The beauty of the colour gives all the objects, people, animals and things the same mode of being: like in a fairy tale. People become plates (nr.35,89-93,117-123), teddy bears are (pregnant) people (nr.52-62), musical instruments fall in love with each other (nr.12), a bull is only a tattoo (nr.104), chess pieces return to being kings, rooks and bishops (nr.85-88), matches become natural disasters (nr.79-84).

The fairy tale brilliant colours give something back to the cleared things that was taken away from them as a form: an "inner self" or "individuality". But this inner self also comes from outside. A gleaming casing surrounds them like an aura. The viewer never tires of looking at it. The illumination of the things and the painting are the consequences of the look of the love they contain, but this love is simultaneously stored in the things and it emerges as the things catch our eye. They behave just like the Madeleine from Proust, also, in itself, a commonplace object. They conserve the time taken by a person and only give up their secret to him when he comes into contact with them again. For a brief moment they restore our youth to us. This is the mode of being that is revealed by the art of Peter Keizer. Only in his paintings do the things display their capacity to conserve as a living present-day the history of people who have lovingly encountered these things in the past.

The painter also chooses the motifs as he instinctively comes across them. Peter Keizer once, apparently paradoxically, said: "You can try to paint anything, but not everything allows itself to be painted". Only the aura of the personal, actively lived and loved time that pops up out of oblivion, can change the article into an object of artistic desire. This desire also manifests itself in the repeats and the series of Peter Keizer's paintings, desire never stops, it always wants more of the same.

By dismantling the things, alienating them, they are stripped of the mist of their functional context. Only these naked objects produce the joy of finding again and reliving earlier times. Through this experience the empty time that is nothing more than a milometer on the road to death vanishes. The "trans-portation" back to an earlier time, our transformation into a younger self, this is the fairy tale dimension of "our" objects. Peter Keizer has revealed this secret of the things to us in his paintings.

Helga Geyer-Ryan is professor of universal and comparative study of literature. She works at the Universities of Amsterdam, Cambridge and Los Angeles (UCLA).

↑ TOP